Break Time

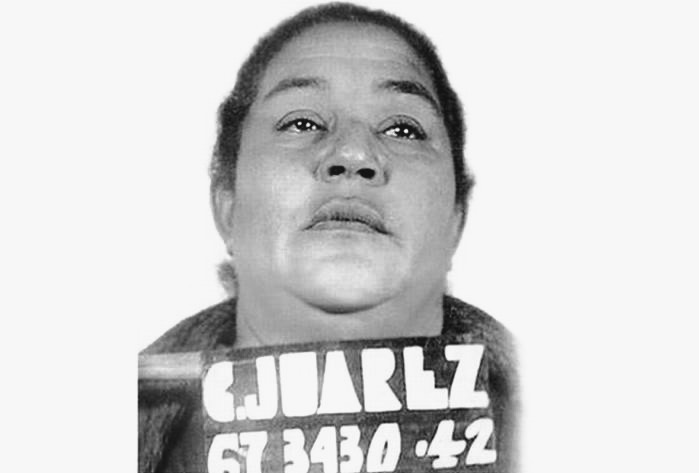

More dangerous than Lucky Luciano

Before she packed her bags for the last time and fled her home in Juárez, Mexico in 1973, with the federal police hot on her trail, Ignacia “La Nacha” Jasso had been one of the most powerful and feared gangsters in Mexico for decades, described by American officials as more dangerous than notorious American crime boss Lucky Luciano.

La Nacha ran 1st drug cartel

La Nacha created the first drug cartel and operated what the US government called the largest international drug operation in Mexico and she led it for fifty years, longer than any other drug cartel leader. She was famous for using violence to expand drug trafficking territory and eliminate rivals who stood in her way, once ordering the execution of eleven drug traffickers one night when they would not cede their drug trade to her. In Mexico, she established the first major drug supply and distribution routes to the US, which decades later were used by the Guadalajara, Juárez and Sinaloa Cartels which helped them scale their drug empires when she was gone. These underworld achievements made her a pioneer mobster in the annals of drug trafficking in both the US and Mexico.

But because of it, La Nacha dodged trouble most of her adult life. She started early in life trafficking drugs, and although it was not easy for a woman to lead an international drug trafficking organization in Mexico, she learned to align herself with corrupt Mexican law enforcement officials, especially the Mexican Policía Judicial Federal to avoid serious time in prison and thrive as a drug trafficker, eventually becoming the first Mexican drug trafficker to control drug operations at the Mexican-US border.

She also appears to have been the first Mexican drug kingpin wanted by the US government for extradition.

While La Nacha has been mostly forgotten and minimized in the history of drug kingpins, the Queen of the North paved the way for the emergence in Mexico of the powerful drug cartel phenomena.

La Nacha’s early life

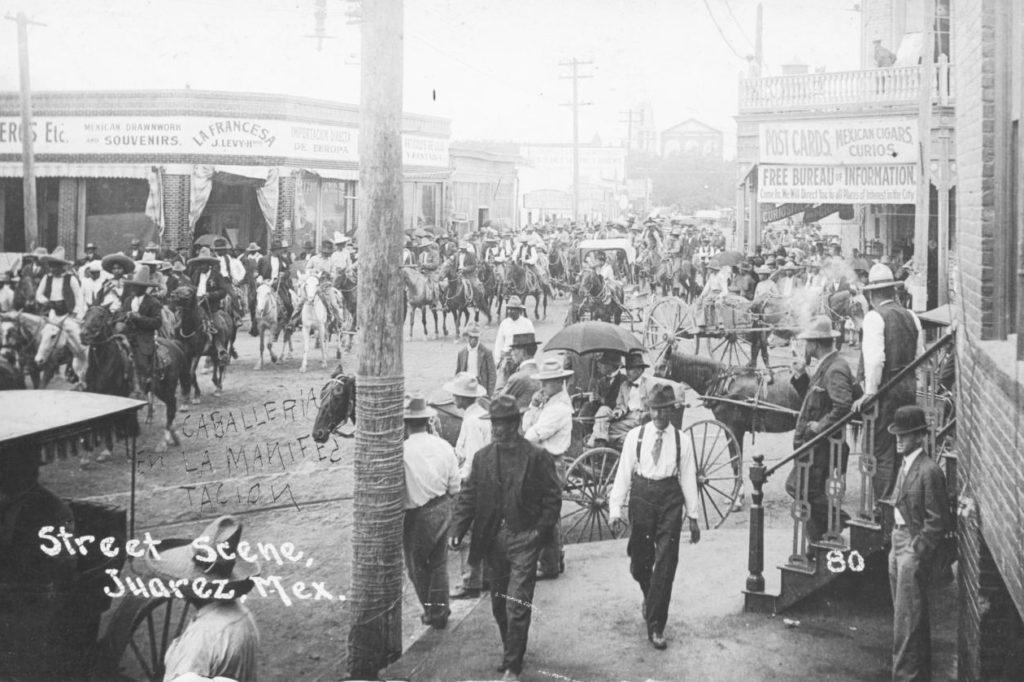

La Nacha was born in the mid 1890s in Juárez, Mexico, a town that borders El Paso, Texas.

During prohibition the population exploded. In 1921, the population of Juárez was 19,451. By 1930, it more than doubled to 39,669. It became one of America’s favourite towns for vices of all sorts, receiving over 400,000 pleasure-seeking tourists a year.

Americans who crossed the border to Juárez came for the brothels, casinos, cabarets, opium and morphine dens and alcohol. It was the final destination for those looking to park 1920s morality at the US border.

Juárez was a town you went to because everything that was prohibited in Texas was permitted there.

Street of the Devil

Juárez experienced a golden age and an economic boom during prohibition. As the cabarets, casinos, drug dens and brothels sprouted up along Calle Diablo – the Street of the Devil – organized crime was not far behind.

The amount of cash left behind by American tourists in Juárez every year was in the tens of millions. La Nacha wanted a piece of it.

In those days, the DEA didn’t exist – the US Treasury Department had jurisdiction over alcohol and narcotics and it mostly focused on the illicit trade of alcohol that passed through the Mexican border.

Early drug mule

How La Nacha got started in the drug trade is anyone’s guess.

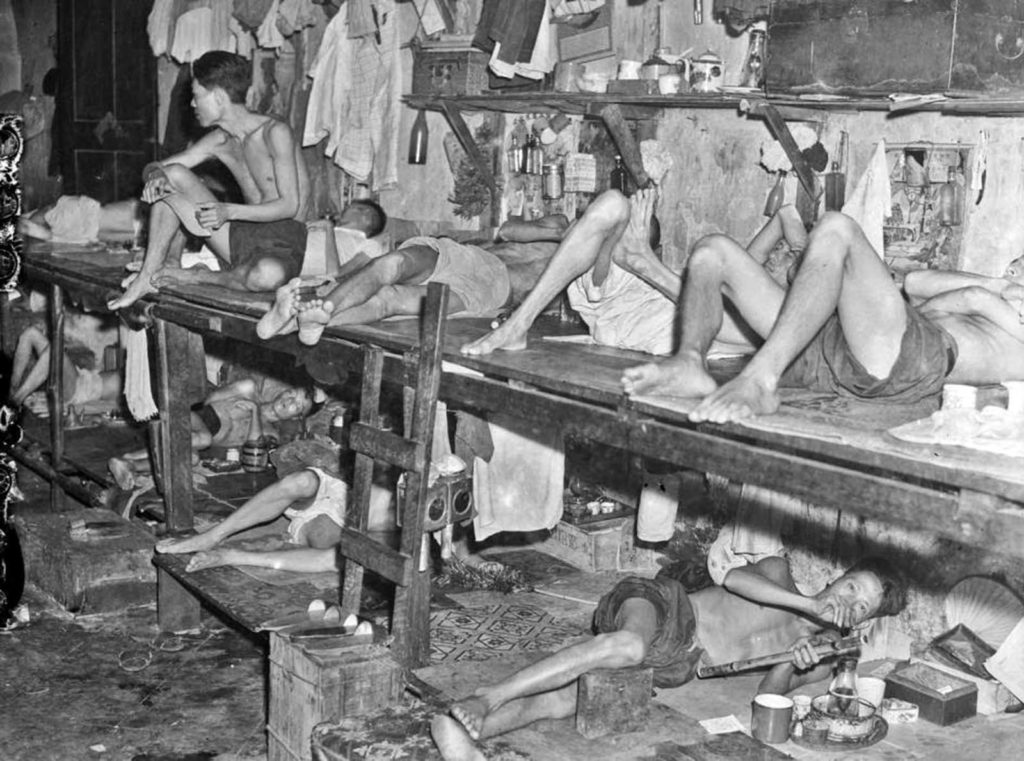

In her teens, she became a drug mule, walking heroin across the border into El Paso, Texas, for local Mexican drug sellers. In the 1920s, US customs and border officials estimated that 60% of illicit drugs brought into the US from Mexico were smuggled in by female drug mules because women were less likely to be searched. The money was good and La Nacha stayed in the business. She had a knack for evading law enforcement.

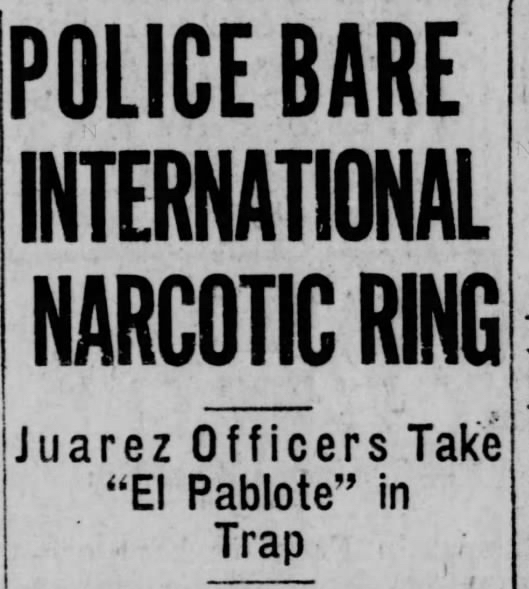

Gambling, brothels, drugs and money laundering

Mexico was gaining a reputation for domestic opium, morphine, heroin and marijuana by the mid-1920s. Poppies had been introduced to Mexico and grown in northern states by Chinese immigrants since the 1800s. It was sold in supervised drug dens, similar to what today could be loosely considered drug safe houses. They also used poppy resin to make morphine, and its derivative, heroin, which were sold at drug dens. In those days in Juárez, heroin was pure enough to be sniffed or smoked.

In Juárez, drug dens were hidden in the back rooms of clubs, cafes and laundry stores, many of which were owned by Chinese immigrants. Often the cafes and clubs also fronted for underground brothels and casinos. Chinese laundry stores were also used to count and exchange cash, loan shark, pay wages and as fronts to launder money. It is believed that the term “laundering” of money may have derived from the use of Chinese laundrettes that fronted for illicit businesses to wash money in order to obfuscate the proceeds of drug dens and brothels.

Drugs were also sold on the street and in homes in Juárez.

In 1920, a number of the drug dens in Juárez were owned by a Chinese immigrant named Sam Hing (some researchers say Sam Ching). Hing sold more than opium, morphine and heroin – he also sold marijuana to Americans.

Caro and Fonseca families sold marijuana 100 years ago

Hing travelled to Sinaloa and other states looking for marijuana suppliers to sell him product and deliver it north to Juárez to meet the town’s growing demand. He entered into a deal with the families of what would become one of the world’s largest drug cartels sixty years later thanks to his unintended support – the Caro and Fonseca families. In the 1920s, Gil Caro, Manual Caro and Rafael Fonseca were small time marijuana growers. They increased production and sold marijuana to Hing.

Gil Caro and Manuel Caro are the ancestors of Rafael Caro Quintero; Rafael Fonseca is the grandfather of Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo. Rafael Caro Quintero and Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo were the founders and leaders of the Guadalajara Cartel, with Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo.

Meanwhile, La Nacha was expanding her drug trafficking activities in the State of Chihuahua and in the US, engaging drug suppliers and arranging shipments, as well as drug distributors in the US, who could expand her reach and move her drugs.

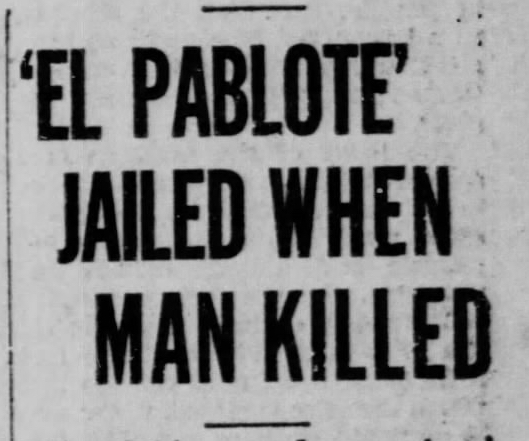

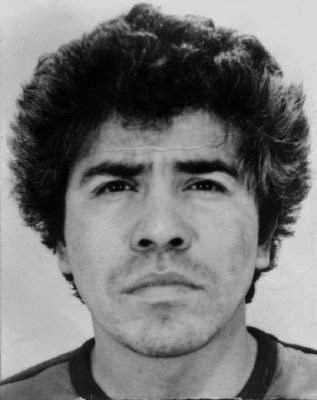

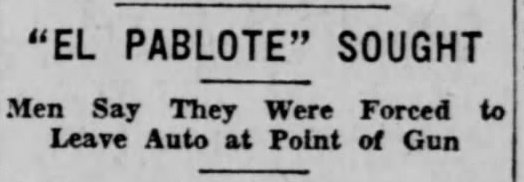

Marriage to King of Morphine

She married a well-known drug trafficker in Juárez named Pablo “El Pablote” González. He was a significant morphine trafficker known as the “king of morphine” on both sides of the border. They couldn’t have been more different – El Pablote was loud, a trigger-happy womanizer, a drinker and an uncalculated risk-taker in your face type of person. La Nacha was a calculated low key risk-taker who was more interested in quiet asset accumulation than cabaret-hopping along the Calle Diablo.

Setting up the La Nacha Cartel

As unusual as their union was, it worked and together, they formed the first Mexican drug cartel, dominating drug trafficking activities along parts of the US-Mexico border. Arrests years later of the La Nacha cartel often involved take downs of 20 to 40 suspected members, attesting to both the organized nature and size of the cartel some 90 years ago.

In the beginning, they controlled just the trafficking of marijuana and morphine into El Paso, Texas and in the State of Chihuahua, Mexico, but quickly expanded to control the drug trade in the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Sonora and Sinaloa.

La Nacha seems to have understood very quickly that she could run the La Nacha Cartel any way she wanted to in Mexico. One day, she set her sights on Sam Hing’s supply business with the Caro and Fonseca families and his Juárez drug dens.

La Nacha kills 11 rivals

In 1925, she ordered the killing of Sam Hing and ten of his associates. They were executed in the streets of Juárez, all in one night. Some of their bodies were dumped in the desert and others in the Rio Grande.

La Nacha is believed to have taken over all of Hing’s legitimate businesses, his illegitimate businesses and his marijuana deals with the Caro and Fonseca families. They were not her only drug suppliers – she bought marijuana grown in Juárez and heroin from Terreón.

El Pablote spins out of control

Although the La Nacha Cartel was thriving, El Pablote was getting out of control. In the course of ten years, he had been arrested over 100 times for various serious charges that included hijacking a car at gun point, operating a drug den, drug trafficking, assault, attempted abduction of a woman from a hotel, murder and sexual slavery. Each time, the charges dropped or stayed.

In 1928, there was considerable heat on him and he moved to El Paso, Texas, while La Nacha stayed in Juárez.

President of Mexico orders arrest of El Pablote

In 1929, he returned to Juárez and continued trafficking. The President of Mexico issued an order for his arrest for trafficking opium. He was arrested and brought to Mexico City for prosecution but a few months later, he was free and back in Juárez, where he and three other men attempted to kidnap a woman from a hotel and force her to go for a car ride with them. He was arrested, released and then arrested again for drug trafficking with 24 members of the La Nacha Cartel. The police promised that this time he would receive a long sentence. He didn’t.

Crime in Juárez was rampant. The mayor of Juárez was accused of accepting bribes from bar and club owners to ensure the local police looked the other way. In 1911, the Governor of Chihuahua sent orders to the mayor of Juárez to close illegal casino clubs and dens and casinos in Juárez six times. Each time, the orders were ignored. The Governor sent in the army and raided a handful of casino clubs operating at the back of saloons and clubs. The mayor was arrested and removed from his post. Days later, the casinos were open again and new ones sprouted up all the time into the mid-1930s.

El Pablote felt that he was untouchable but his days were numbered.

In 1930, he walked into a bar on Calle Diablo, plastered, and shot and killed a police officer. Some months later, he shot and killed a second police officer when he was drunk at a bar. He boasted the next day that he had eaten owls for breakfast. An owl was the term for a police officer who worked a night shift.

Two months later, he walked into the Popular Cabaret and never walked out. He was killed by a police officer in the bar, who said it was self-defence because it was El Pablote.

At his funeral, La Nacha promised to get revenge. “I promise you, darling, I promise you, dear”, she was reported as saying, “I will kill the one who killed you.” She never did. The truth was, many members of Mexican law enforcement were on her payroll.

First narco corrido was about El Pablote

The story of El Pablote became famous in Mexico and he was the first drug trafficker to have a Mexico drug ballad (known as a narco corrido) written about him. It was called “El Pablote.”

While not the first narco corrido, it is the first one about a narco. Composed in 1931, it recounts the story of how El Pablote was a well-known drug trafficker and how he was killed. It describes him as a violent gunner who terrorized the border.

Narco corridos are popular in Mexico and narcocultura – to be the subject of the first narco corrido helped to grow the legend of El Pablote and La Nacha.

After death of El Pablote

After El Pablote’s death, La Nacha ran the cartel herself, strengthening her drug activities as far south as the State of Michoacán.

The story of La Nacha executing Sam Hing and his men in the streets of Juárez to take over his drug business served as a reminder not to cross her.

Violence, corruption and loyalty

Like any drug cartel, La Nacha made deep alliances with corruptible Mexican law enforcement agencies in several states and with politicians to ensure she could operate the drug cartel unimpeded. She did things that later became standard procedure for cartel leaders but that no one had done before – for example, she had law enforcement issue her a set of credentials that allowed her to travel without being stopped or arrested across Mexico – a tactic that the Caros and Fonsecas emulated when Rafael Caro Quintero and Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo formed the Guadalajara Cartel. If she was going to run drugs up and down the coast, she needed to ensure that her team wouldn’t be arrested along the way.

Long before cartel leaders like Pablo Escobar and Joaquín “El Chapo” Archivaldo Guzmán Loera thought of the idea, she rallied support among the poorest of Juárez’s families by stepping in where governments didn’t, setting up charities, and food programs for families in Juárez which helped build a base of loyalty towards her among the people of Juárez.

Those three things – violence, corruption and loyalty – helped La Nacha remain relatively untouchable as a major drug trafficker and was the operational model copied by many drug cartel leaders decades after her.

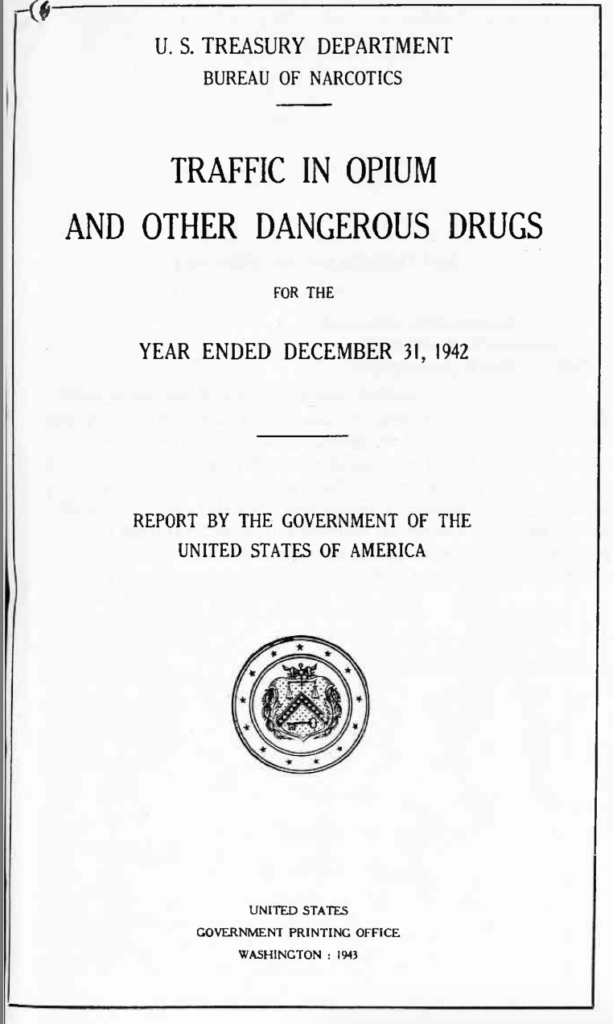

Federal Bureau of Narcotics identifies La Nacha as major drug trafficker

In the mid-1930s, the US Treasury Department became increasingly concerned with drugs coming in from Mexico. Harry J. Anslinger, the director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, an agency within Treasury, set his sights on La Nacha as the main Mexican drug trafficker causing harm to the fabric of American society. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics later merged with another agency and became the DEA. A virtual tour of Anslinger’s life and impact is here.

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics described La Nacha as the leader of an international drug organization that ran the largest international drug trafficking operation between Mexico and the US, and one of the major suppliers of illicit drugs trafficked in the US. Director Anslinger said that she was the brains behind Mexican drugs showing up across America in several cities [with supply routes and a drug infrastructure] with a reach that included New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Seattle.

In 1933, she was arrested for selling heroin in her home. She contested the charges, alleging that she travelled to places such as Sinaloa and Jalisco to sell dry goods. The charges did not stick.

In 1939, La Nacha moved around and spent some time in Torrerón, Coahuila, and in Jalisco where she invested in poppy fields and in Guadalajara, where she built a lab to manufacture morphine and heroin.

Mexico becomes major US illicit drug supplier for 1st time

1942 was an important year in US-Mexican drug history and policy. That year, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics reported that there was a shortage of illicit morphine and all of the illicit versions that entered the US were from labs in Guadalajara. They also reported that, for the first time ever, Mexico had become a major supplier of illicit drugs into the US, joining the ranks of Iran and Cuba, with illicit drugs from Mexico showing up in every major city in America. Anslinger reported that while illegal drug distributors and dealers were being arrested and prosecuted in the US, the problem could only be resolved if producers in Mexico were stopped. That meant La Nacha.

A sting to catch La Nacha

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics set to work infiltrating the La Nacha Cartel in Mexico. Later that year, working undercover, agents met several of her key facilitators – her lawyer, chauffeur and her chemist in Guadalajara. They were taken to poppy fields she owned in the mountains outside of Guadalajara, and to her lab where she manufactured morphine and heroin from raw opium. La Nacha clearly thought in a criminal way like no other mobster, for in order to protect the lab from being busted by police, she built it in the office of her lawyer.

Bureau agents set up a sting to entice cartel members to smuggle drugs manufactured by La Nacha into the US.

The sting operation worked and in June, 1942, several La Nacha cartel members arrived in Texas with morphine concealed in the gas tank of a car. Two days later, other cartel members delivered tins of opium to undercover agents in El Paso. Thirteen were indicted, including La Nacha, in San Antonio, Texas, for drug trafficking.

La Nacha sought for extradition

Anslinger sought the extradition of La Nacha which was denied by Mexico. In order to effect service upon her of the indictment, Mexico agreed to arrest La Nacha. She was arrested and charged with administering morphine to an addict at one of her drug dens and served with the indictment from Texas.

Rather than extradite La Nacha from Mexico, the Mexican government exercised wartime legislation to send her under remand to Islas Marias, the Mexican prison on an island off Mexico for dangerous criminals. She was then transferred to a jail in Juárez, where she continued to operate the cartel with the help of her children. She was released when the war was over.

Move to Guadalajara

La Nacha moved to Guadalajara after prison for the same reason so many others flee to southern Mexico – to lay low and run underground operations away from the spotlight. It is believed that she spent much of the 1950s and 1960s between Guadalajara, where she could manage her drug lab, and Juárez, overseeing the trafficking operations.

Several of her children and grandchildren continued the drug businesses in Juárez. Two of her grandchildren, Héctor Ruiz González and Eduardo Amador González, became leading drug traffickers in the La Nacha Cartel in the 1960s. Several times in those years, members of the La Nacha Cartel were arrested but not La Nacha herself.

In 1961, Mexico’s Policía Judicial Federal issued an extraordinary statement to the media, stating that it was untrue that La Nacha was associated or involved in drug trafficking activities in Mexico, and that her immense wealth made such activities unnecessary. They accused US law enforcement of invading Mexican territory for drug investigations, leading innocent citizens into the US where they were arrested and narcotics were planted on them. The message was clear – the Policía Judicial Federal had the back of La Nacha.

La Nacha owned brothels, poppy fields, drug dens, ranches and drug labs

The US government nonetheless continued to seek her extradition continuing into the 1970s. They informed Mexico that their intelligence showed that La Nacha led organized criminal drug trafficking across Mexico and into the US, and owned prostitution houses, poppy fields, ranches, drug dens and drug labs. They wanted La Nacha, her grandson, Héctor Ruiz González, and Jose Roberto “El Picho” Zamora, whom they considered the kingpins.

Close to the end

It was not to be because by the mid-1970s, it was close to the end for everyone in the La Nacha Cartel.

La Nacha’s grandson, Eduardo Amador González, spent years in jail in the US, appealing an arrest in 1965 and a subsequent conviction for heroin trafficking. 33-year-old Héctor Ruiz González was killed in a suspicious car accident in 1973 – taking them both out of the picture and weakening the organization. The US government upped the pressure on Mexico. They told Mexico that she was the number one Mexican narcotics trafficker in the US and that La Nacha was more dangerous to the US than Lucky Luciano.

Who could be more dangerous than Lucky Luciano? Mexico was persuaded. Mexican federal narcotics police issued a warrant for her arrest and let it be known that she was a fugitive.

La Nacha went underground. To disable her activities, officials reportedly seized US$3 million from one of her bank accounts in Juárez and US$4.5 million in cash from her safety deposit boxes.

La Nacha was never captured and by 1976, the Mexican government was reporting that the State of Sinaloa was the new epi-center of drug trafficking for the whole country with more drugs trafficked, imported and exported from there than anywhere else in the country.

La Nacha died in 1977.

Guadalajara and Juarez Cartels fill void

After her death, Raphael Caro Quintero and Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo emerged to fill the drug cartel void in both Guadalajara and Juárez, her two main bases of operation. Together with Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, they created the Guadalajara Cartel and the Juárez Cartel, relocating the nephew of Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo, Amado Carrillo Fuentes, to run operations in Juárez, key for border drug routes and marijuana fields in Chihuahua used by La Nacha.

El Chapo started his criminal career as a sicario for Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, and later for the Guadalajara Cartel with Gallardo, Quintero and Carrillo.

Mobster legacies of La Nacha

Many of the mobster legacies attributed to some of the major Mexican cartel leaders, such as Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo and Rafael Caro Quintero, are in reality legacies of La Nacha that they learned from her decades-long relationship with their families.

She created the violence, corruption and loyalty blueprint for later cartels to follow and did the hard work of establishing the drug trafficking infrastructure (supply, distribution and networks) in the US and Mexico that they were able to use to rapidly scale in the drug trafficking business. She showed by example, terrible as it was, the murder, violence and ruthlessness needed to take control of drug territories from rivals and how to run drugs up the coast into the US and move the proceeds back down in ways that were undetected. She also showed, by example, how to infiltrate law enforcement agencies, in her case the Policía Judicial Federal, and buy protection for drug operations and remain relatively free from prosecution.

Drug cartel leaders have come and gone and a few have reappeared but none have ever been able to operate a resilient sustaining drug cartel for over 50 years like the Queen of the North.

Why an important criminal figure in the history of organized crime in Mexico and the US has been ignored in history and narcocultura is probably attributable to the fact that history generally has struggled to present a diverse and inclusive picture of the past. La Nacha is no hero but its important to evaluate the role that women played, and continue to play, in the formation of transnational criminal organizations and the context of how their networks function in order to have enhanced visibility to detect, deter and control its harmful effects on the rule of law.

End Notes

Family of La Nacha & El Pablote

No research has been done on the identity or whereabouts of the descendants of the infamous La Nacha and El Pablote. We know that among the real property La Nacha owned, directly or indirectly, was at least one ranch in Cases Grandes, Chihuahua, where Héctor Ruiz González lived with his wife and children before he was murdered in 1973. Héctor’s children were raised in Cases Grandes, and there may be direct descendants of La Nacha and El Pablote in Cases Grandes. The same is true of Juárez.

One wonders if Roberto “El Mudo” González Montes, who lives in the same town of Cases Grandes, who is believed to lead the La Línea cartel, may be a relative of the La Nacha González clan. La Nacha’s old marijuana supplier, Rafael Caro Quintero has allegedly hooked up with El Mudo and La Línea. Why La Línea; why a González; why Cases Grandes?

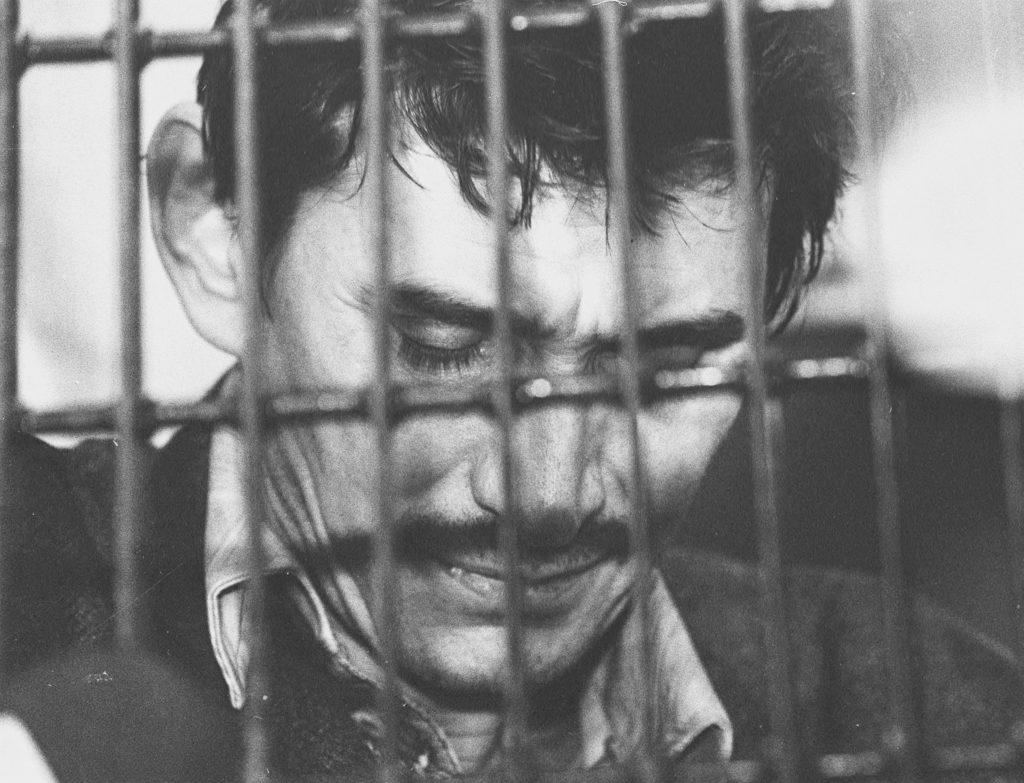

Rafael Caro Quintero, Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo & Amado Carrillo Fuentes

A lot has been written suggesting or stating that Rafael Caro Quintero became a drug trafficker in 1980, started an international drug cartel that same year which became successful immediately with suppliers and distributors lined up to distribute drugs across the US. That narrative isn’t accurate.

Rafael Caro Quintero’s grandparents, and many members of his extended family, were marijuana growers over 100 years ago.

We know that they sold illicit drugs from their property to La Nacha in 1925, and before her, to Sam Hing before 1920, and Hing arranged for ways to ship it to Juarez for several years before La Nacha took over his business. We also know that in 1966, Rafael Caro Quintero grew marijuana and then poppies on a full-time basis with his mother on their property, and they sold it to many distributors as far north as Chihuahua. At that time, La Nacha was living in Guadalajara running her drug lab, and buying drug as a wholesaler from the Caro Quintero and Fonseca Carrillo families. By then, they had all been in the illicit drug business together for forty years.

Rafael Caro Quintero and Ernesto “Don Neto” Fonseca Carrillo were both suppliers to La Nacha but that was not the only connection between them – Rafael Caro Quintero knew Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo since birth and their families inter-married.

Rafael Caro Quintero did not acquire wealth overnight. By 1980, the DEA had already located over US$1 billion in assets acquired from criminal activities held by the then 28-year-old Rafael Caro Quintero. He had that much wealth because he had been in the illicit drug business since he was 14. By the time he was 37, he held hundreds of millions of dollars in bank accounts in Panama, Luxembourg and Germany. Recently, he has admitted that he trafficked drugs for 31 years.

Around the time of the start of the decline of the La Nacha Cartel, Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo sent his nephew, Amado Carrillo Fuentes, to take over organized drug activities in Juárez and the surrounding area in Chihuahua. With La Nacha’s family gone, he needed someone he could trust so far away to continue to find a market for heroin and marijuana the family produced and supplied up north. Amado Carrillo Fuentes obliged his uncle and eventually helped form what became the Juárez Cartel.

Rafael Caro Quintero was arrested in 1985 for the murder of DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena Salazar, and was incarcerated in Mexico until 2013, when he was released. He is wanted by the FBI and a US$20 million award is available for information leading to his arrest.

Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo was arrested in 1985, also for the murder of Kiki Camarena, and incarcerated in Mexico until 2016, when he was released and confined to his house.

Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo & El Chapo

Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo was arrested in 1989 and convicted of various serious crimes including for the murder of Kiki Camarena and remains incarcerated in Mexico. He wrote a short biography of his life here, in which he says that his children, were given visas to enter Canada, and moved there to “study.”

El Chapo was one of the first sicario hires of Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo and later he worked for the Guadalajara Cartel for the short time it was operational. When the Guadalajara Cartel collapsed, El Chapo led the Sinaloa Cartel in 1988. In 2016, he was captured in Mexico and extradited to the US, where he was convicted of numerous criminal cartel-related offences. He is currently incarcerated in the US. In 2013, he came out of hiding to pay a visit to Rafael Caro Quintero, when the latter was released from prison.

El Chapo, Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo and Rafael Caro Quintero are all from Badiraguato, Sinaloa, Mexico and they knew each other since they were children.

Forfeiture of proceeds of crime

The idea of forfeiting proceeds of crime in terms of cash from criminal activities was invented in Mexico. The first drug trafficking proceeds of crime forfeiture of cash by a government occurred in Mexico in the 1940s, in connection with the forfeiture of the wealth of a different female drug trafficker who was accused of trafficking heroin to Canada. Mexico then used its forfeiture tool in 1973, to seize million of dollars in cash from La Nacha.

Chinese clubs

To this day, Chinese foreign nationals in the US, Canada and Hong Kong continue the club system for organized illegal gambling and loan sharking, often accompanied by prostitution. Clubs charge high membership fees and are open only to Chinese foreign nationals, often only of Han ancestry. Chinese clubs also serve other functions such as networks for legal and illegal capital raising efforts. Clubs in Hong Kong and Canada also often function as private lunch clubs.